A

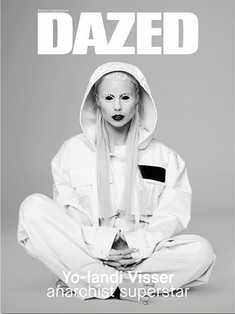

desperate director discovers a skateboarding muse clued up on Melvin Van

Peebles, John Waters and Kubrick. Originally published here.

It is

113 degrees in Downtown Los Angeles. El Salvadoran parking lot attendants stuff

their pockets with cans of ice cold Coke Zero, enjoying the cool moisture on

brown skin. I’m not there, of course; I’m a few miles northwest, chillaxing in

the shade by my infinity pool. You can see the smog hovering above the city

from my 1938 estate, a panoramic airborne sludge of green, orange and dirty

white, a cap of toxic waste floating all the way from Downtown to Century City.

I sniff -- even up here in these Hollywood hills, the air has a faint whiff of

bongwater, especially on hot days. I like it, it makes me feel relaxed. So I

close my eyes, rest my hand on my crotch and imagine how my obituary will read.

“Remembering

Desmond Furie, born on June 16, 19--, a super fucking cool independent film

director, screenwriter, producer, set decorator, cinematographer, actor, who

established himself with one teen exploitation movie in 1997, a genre-defining

masterpiece of experimental storytelling called A Minor,

and then he made another cool film that was equally amazing (we’ll insert the name

later – Ed.) Every year since then he observed himself

grow further and further removed from the youthful subject matter that had made

his name until today, the first day of his sixth decade, when he languishes in

loose-skinned decrepitude, exacerbated by years of drug experimentation. His

favorite song was “I Just Can’t Be Happy Today” by The Damned. His final words

were…’It’s a trap!’ Did we mention he was cool?

The

kids love my shit, always have, because it’s real. It

speaks to them. My work is nasty like bongwater smog, I show them giving head,

getting head, doing whippets, shooting up, doing the shit they actually dig.

Do you

know what it feels like to peak on your first project? Do you, though?

Google

Maps says it’s gonna take me 20 minutes to get to the intersection of

Washington and Crenshaw, which is where Caviar lives.

Caviar

is a rapper. Caviar’s my only hope.

A

Minor happened and suddenly everybody knew my name. I’m getting

money thrown at me by Japanese clothing brands, by indie boutiques in Paris,

Hedi Slimane wants to bro down, Terry Richardson is taking my photo for i_D

magazine, Courtney Love and Winona and Kate Moss want to chill with Desmond.

What’s next, everyone wanted to know.

What’s

next? Fucked if I know. I mean, I had never thought that far ahead.

My

manager, TC, always asking — what’s next? Fuck you, I

said. I’m an artist. My creativity adheres to no calendar, except its own.

Between you and me though, the truth was…I had blown my creative load. Then

some asshole in the trades said shit like “Could it be that Desmond Furie’s

notorious directorial debut would also be his swan song?” And that’s when I

started getting high.

I open

my eyes, see that the sun has set. My Rooibus tea is cold, so I dump the dregs

into the infinity pool. One time, on a particularly dark night of the soul, I

tried to guesstimate how long it would take me to drown in it. Like three

minutes? Eight minutes? How long before my heart stopped beating, after my

lungs had filled up with water? An hour? Whatever the answer, it was definitely

less time than it takes for me to come up with a good idea.

This

creative anxiety is crippling, I tell you. I’ve tried to remain positive about

my little thoughts of suicide. They’re a motivator, a reminder that I

don’t got this, that something needs to change. An egomaniacal

artistic mind trapped in a state of torpor — there is no more twisted fate. One

day I did the math. It’s a simple equation: creative dysfunction + isolation =

wanting to kill myself. I couldn’t do anything about the creative dysfunction.

But the isolation, I could address. I decided to get a girlfriend.

Her

name is Tiara Loomis, she’s an actress, and she is 22. I met her in AA. She

said she was a fan of A Minor. Duh, I thought. I am not

hurting for pussy, and never have. It got crazy when social media started up --

LiveChat, Buzznet, Yahoo Chat, MySpace (before it got lame), Facebook, Twitter

and of course, Insta — suddenly I was getting pussy and tittie pics from girls

all around the world, every day. The Russians…the Russians.

But in

my opinion, LA girls are the best. They get it, those bitches are creative too,

even the groupie types usually got something creative and interesting going on,

some kind of t-shirt line with their best friend or they’re stylists or they

take photos of bands or they write haikus and web series and hour-long dramedies

or some shit.

Tiara

came over, read my tarot cards, told me my chakras were blocked, and fucked me

like she was being paid for it. She promised she would never leave me, so I let

her move in.

But

things were starting to feel strained between us. She said I was boring, my

negative hyper-emo outlook was interfering with her ability to create or some

shit. A few months ago she stopped wanting to bone. Then last week, the worst —

she called me “grumpy cat”.

“FUCK

GRUMPY CAT!!!” I screamed.

“Exactly!”

she yelled back, looking like a mad Asian Disney princess.

Today

she's in Milan, meeting with some fashion designer about modeling in the

Fall/Winter campaign. I mean, she didn’t need to go, it’s not like she needs

the fucking money. She went to get away from me.

It’s

obvious —even though I directed her favorite film of all time, bottom line, my

girlfriend doesn’t think I’m cool any more. Fuck.

I thought

about Eve, my first girlfriend. She was 12 when we met. She had these eyes,

blue-white like a wolf’s. Her eyebrows were white and she wore a Led Zeppelin

t-shirt and short shorts. She gave me vodka and told me I was cool, and when my

fingers brushed against her push-up bra, suddenly everything seemed OK again,

even though mom was dead and grandma was crazy and dad was taking me to his AA

meetings where the old alcoholics always asked me “you getting laid?” I was

what, 10? After that day with Eve, I could finally look those old alcoholics in

the eye and say “yes”.

When Grandma

gave me my first camera, Eve really encouraged me to use it. I got pretty good

at taking pictures, mainly of myself and Eve and the other hood rats. Kids just

got used to having me and my camera around, and after a while it was like I was

invisible. They let me take pictures of everything they did. Pictures of things

that weren’t supposed to happen. Things we did when our moms and dads weren’t

looking.

Eve was

my girlfriend for years. She sent my stuff to some hip magazines and they liked

it. The weirder, the more fucked up, the better, they said. I was making a name

for myself. “You should make a feature film,” Eve told me. “Leave town, be a

director, go to New York, Hollywood.” I knew she wasn’t coming with me, and I

never saw her again after I left.

It

took several years for me to get established. By the time the script for A Minor came around I was already well into my 30s. A very

hot skater called Foot Head collab’d with me on the A Minor script. (When I say he was “Hot” I mean zeitgeistally hot, of the moment, au courant. Not “hot” as in fuckable —

I don’t mess with boys, contrary to the rumors.)

But I

was still super down with the program. I knew what was up, and my fans were the

coolest kids in town.

I

slouch into the kitchen, check my phone. “MU”, I had

texted Tiara several hours ago. I saw the “read” receipt. No answer.

Anxiety

rises in my chest, so I take off my silver locket and open it up. Once upon a

time I kept it filled with cocaine. Today, it contains a blend of pure,

high-grade valerian root powder. “Nature’s downer,” Tiara says. I snort a bump

of V, shower, and get dressed. I put on a black Chelsea Wolfe concert tee,

black ACNE denim, black VANS and prescription self-correcting sunglasses and

get into my black Audi. I set the air conditioning to “max”. Kendrick Lamarr,

Christian Death and Japanese experimental noise on shuffle.

Some

British music writer had sent me some of Caviar’s videos. His shit was psycho,

next level. Both visually and lyrically, this kid’s vision was deep. He

reminded me of myself when I was 16 — wherever he’s not supposed to go is where

he’s at. Rape, scat, swastikas, anal in graveyards, the occult, the KKK, Chola

girls, depression, Buddhism, unicorn sex — these were the things he rapped

about.

How

some African American skater kid from South Central could be clued up on

Crowley and Jodorowsky and Jung and Melvin Van Peebles and John Waters and

Kubrick and Spike Lee and Les Blank made no sense to me. It was like he had a

direct line to my own lifetime’s worth of pop culture influences, the

difference being — he was 44 years younger.

Maybe

it was the internet, making it easy for these Millennial motherfuckers to appropriate

everything that’s cool with just a click. I wished it had been that easy for

me. But I knew Caviar wasn’t just some poser. He was the real deal. I wanted

in. I wanted him.

There

was one YouTube video in particular, in which Caviar performed some kind of

occult ceremony on his friends. His eyes bled tears and his teeth fell out and

all the children collapsed on top of one another on the dirty floor of some

shit house.

16

years old. What was his problem, why did he hate everything so much, I

wondered? I looked into the dark, angry eyes staring back at me on the computer

screen and felt a warm kinship. “This kid doesn’t want to be alive any more

than I do,” I realized, happy.

I did

not know what had happened to Caviar, why he was filled with the same dark fear

that dwelled in me. Maybe he too had lost his momma before he had even a chance

to get to know her. Maybe he had unwittingly shoved his protégé into the arms

of death, much like I had with Foot Head.

There

were no amends to be made there, and I would carry that with me for the rest of

my life.

Foot

Head was looking for a new high. We met up in Seattle and I scored him some

blow. No big. The cocaine in Seattle had always sucked but around that time was

when they were cutting it with that animal de-wormer levamisole that

metabolized into some lethal shit in your body and wound up killing a bunch of

people one summer. Foot Head was one of

them. I was so bummed I went back to LA and scored some street dope in

Downtown, and as luck would have it, I was busted by undercover.

TC, my

manager, said he had had enough. “One more arrest and you’re finished,” he

said. That’s when I, Desmond Furie, legendary for my resistance to sobriety,

finally decided to get clean.

I

worked the Steps alongside all the other A-list out-of-work substance fiends in

town, admitting I was powerless over alcohol, acknowledging that my life had

become unmanageable, and realizing that I was, on most days, the oldest

motherfucker in the room. I made all kinds of amends, including financial

amends to the church goers in Portland whose holy water I had spiked with LSD

that one time. They were going to prosecute but said they’d prefer a sizable

annual donation instead.

The

summer I got sober the fires burned the green slopes around my home, charring

the chaparral gardens of Dante’s View and Captain’s Roost. That brush fire was

the last time I had felt excited about anything. Until Caviar.

This

morning, I sent TC a text. “I think I have my new movie.”

Caviar

was elusive — no contact info on his blog — but I managed to track him down by

asking my publicist, who also represents GZA and the Wu, to Tweet at Caviar.

Before long, I had the kid’s phone number.

“Tell

him to meet me at my grandmother’s hair salon,” Caviar tweeted back. I knew

better than to try calling him — kids only take phone calls these days if they

think someone has died.

As I

drive, I picture him throwing his skateboard to the ground, using his left leg

like an oar to propel himself down the street. Steady, with the clack-clack of

hard wheels on concrete, burning through neighborhood after neighborhood,

drowsy pink bougainvillea rustling as he shoots by.

I pull

into a strip mall occupied by a liquor store, a bar, and a hairdressing salon

called Addictionz. Caviar is waiting for me, sitting on the curb, his

skateboard rolling from side to side beneath his sneakers.

The

whole city is burning up, but Caviar’s hat is on, floppy ears absorbing the

rivulets of sweat that tumble from his temples.

As I

get out of my car the look on his face says it all — “some old director dude

wants to meet me today, and my manager says I should just do it.”

He

sees right through me, and I know it. Fuck.

I

watch Caviar pull out a bundle of keys and unlock the door to the salon.

Inside, ragged leather chairs are haphazardly positioned in front of dusty

mirrors. The lighting is unforgiving. Styrofoam heads in full makeup are

crowned with cheap wigs on a shelf. There is no air conditioning and I feel my

body heat billow beneath my tee shirt, warming my silver locket as I follow

Caviar into a small apartment at the back. It smells yeasty in there, like old

cheeseburgers.

A

framed portrait of Jesus Christ sits on the mantle. The cheap bamboo blinds are

drawn all the way down and the kitchen surfaces are grimy. An eviction notice

on the counter makes me wonder where Caviar’s grandmother is, and if she is

older than me.

“I

really dig your rhymes,” I say, feeling like a dumbass the second the words

leave my mouth. Caviar doesn't respond. His silence hurts my feelings. Why isn’t he speaking? Why am I here? Doesn’t he know who I

am?

“I

forgot to jerk off today,” are the first words out of his mouth.

I

sigh, relax, and laugh.

“Oh

yeah?”

“Yeah.”

Caviar

smiles and pulls a blender out of the cupboard. He takes a bag out of his

pocket and waves it in the air. It contains at least an ounce of weed.

“I

don’t get high any more,” I tell him. He smiles.

“That’s

too bad.”

Caviar

pours the weed into the blender. I wonder why. He seems intent, focused, as he

opens up his backpack, pulling more plastic baggies from its depths. Powders,

herbs, pills and liquids; he drops them all into the glass jug. Another baggie,

filled with a yellowy white powder of unknown composition. Next up, a green

liquid. Robitussin. Next up, another brand of cough medicine, this time red.

Caviar

pours the whole bottle into the blender.

“One

time we were shooting in TJ,” I say. “I mean, shooting a film — and in the

regular drug stores they sell everything — like, everything. Morphine,

dialudid, oxycotin whatever. And the beer’s cheap as shit. You ever been to

TJ?”

I knew

Caviar was going to make me drink whatever that evil poisonous concoction he

was making. Every single possible Class A, B and C substance on earth is in

that smoothie. I mean, I have done a lot of drugs in my life —but never all of

them at once.

I

watch Caviar walk to the fridge, pull out a 24 oz Pabst Blue Ribbon, open it

with his teeth, and spit the cap onto the floor. He pours the remaining beer

into the blender. The mixture is alive, foaming, mottled pink and gross

and green, looking like the smog as viewed from my infinity pool. The lid goes

on the appliance, and Caviar hits “blend”.

A few

minutes later, Caviar pours the mixture into two red plastic cups, and hands

one to me.

Under

the heat of Caviar’s glare, I recall the deranged eyes of the armed Congolese

border patrolman he met in 2002, back when I was still traveling international

brothels and getting high. My guide had urged him to remove his Aviator

sunglasses — “Mr Furie, take them off, it will placate.” And it had worked. It

had placated. I take off my prescription self correcting sunglasses and make true

eye contact with Caviar for the first time. Shit. No placation possible. He can

sense my desperation, he knows I need him more than he needs me. This situation

is already out of control.

“You

with me now?” Caviar says, holding out the cup, holding my gaze. “'Cause I only

work with family.”

I

think about family for a second. Father dead. Mother dead. Sister obese. Tiara

fucking Italian lesbians. TC isn’t returning my calls. The only family I have

are the kids. The little psycho scumbags who understand me, because I

understand them. Because I am down with the program. That’s my family, right

there.

I look

into Caviar’s eyes, black holes even darker than they had been on the screen in

the YouTube video.

He

swallows from his cup, slow and hard. His Adam’s apple throbs. He gives no

fucks. He’s crazier than I am. He’s all I have, and he’s waiting for me to

prove what we both need to be true.

That I

am cool.

“Shit.

I could be catering to some bitch right now.” Caviar is losing patience.

My

hand is shaking. I grip the red cup, and ready myself. I down the mixture, vile

chemicals numbing my gums. A few seconds later I lunge toward the kitchen sink

and throw up.

Fade

to black.

About

15 minutes or 15 hours later — who knows — I realize Caviar and I have left the

salon. We are in a liquor store. These are the only hard facts I can establish.

I am

experiencing a familiar kind of delirium, the kind in which panic is

accompanied by extreme physical ineptitude.

I

search for my silver valerian locket, and my hands feel like paddles as they

try to open the antique clasp. I pour the contents of the locket into my

mouth, and it tastes like the vilest most ancient cinnamon.

My

eyes are wide open, I think, and yet my vision keeps shutting down every few

seconds, like a camera shutter. Liquor store, black, tube lighting, black,

Cheetos, black, store clerk, black. Store. Clerk. Store. Jerk.

I

stumble over to the guy behind the counter. “Hey jerk. I need all your

plant-based sedatives,” I say, aware of a cloud of valerian puffing from my

mouth. I cling to the counter for balance.

Before

he can answer, I feel Caviar’s arms around me, dragging me out of the liquor

store. I collapse on his wiry frame and he laughs, and I am amazed he can walk

without clinging to the walls. Balance and gravity are foreign concepts, echoes

of a time long forgotten.

Caviar

lies me down and from the hard discomfort in my back I intuit that I am lying

on his skateboard. My arms and legs are splayed as I feel my body in motion.

Caviar is pushing me along the sidewalk. I wish I could lift my arms, but I

can’t, so my fingernails scrape on the sidewalk. Clack,

clack.This

is no way to travel, I decide, the words appearing in a thought

bubble above my head. Clack, clack.

I

wonder where my iPhone is. I wonder if Tiara has texted back, if TC is coming

to get me. I can’t get arrested again, I just can’t. Even for this kid.

I am

aware of light, dark, approximate shapes, vomit and now the blood which seems

to be pouring from my nose. How did that happen? A scream. Who’s screaming? Am I screaming? Maybe I am.

My

mind fills with gospel music and thoughts of old people on motorized scooters.

So. Many. Thoughts. Government is not the solution and government is

not the problem. Medicare is socialized

medicine. I am on Medicare right now you motherfuckers and you’re going to pay

for it.

“Um…you

guys OK?”

A

shadow leans over me. I’m still prostate on Caviar’s skateboard and Caviar is a

few yards away, peeing in a mailbox.

“We

need PVC pipe, PVC primer, a drill and some Aquanet, for ignition,” I say,

remembering how fun it was when me and Eve would sneak out and shoot potato

guns, getting high off the tubular thunk the potatoes made

as they traveled to the stars. “And potatoes, lots of potatoes. We need to

defend ourselves.”

The

shadow backs away, slowly.

I

looks up at the stars, remembering what my birthday horoscope said that

morning. “No pressure, Libra, but as things are now, you might want to evaluate

your career. Is it working out well?”

My

phone. Here it is. Why can’t I downward scroll? What the fuck is wrong with my

iPhone? I dial a number. Any number. Someone answers.

“Eve…we

don’t have Aquanet,” I whisper.

“Desmond?

Are you high?”

“Eve?”

“No

Desmond, it’s TC. I’m at dinner. Where the fuck are you?”

“I’m

in Crenshaw. I found our kid. I found him, TC. It’s going to be great.”

“You’re

high, aren’t you Desmond. Fuck!”

“I’m

higher than any human being, ever.”

“Fantastic.

OK, well let me make this crystal clear, Desmond.”

“Uh

huh?”

“I’m

done with you. Done. Don’t ever call me again. Asshole.”

TC

hangs up.

Talk

about a buzzkill, man. I get up slowly, pick up the skateboard, and look

around. I’m feeling strangely lucid. Clarity.

Fuck

TC. Fuck Hollywood. Fuck Grumpy Cat being more popular than I am. I’m going to

make this film with Caviar, on my own, and release it on my website, no

distributors, no BS. My fans can pay to download the film, and I’ll shoot the

fuckin’ thing on my iphone and crowdfund the entire production on Kickstarter.

You can get those Moondog lenses and attach them to smart phones, that Filmic

Pro app. Fuck RED. Fuck everything.

I’ll

sell my house. Because my infinity pool is the least indie, least cool thing

that ever happened to me. I’ll move into a studio apartment in Siverlake. Or

better, Boyle Heights. I am an independent filmmaker on the cutting edge, a 60 year

old teenager and my life is my fucking art. Where is he?

I get

on the skateboard, push off. Clack clack. There’s a

breeze…sweet Jesus there’s a breeze running through what remains of my hair.

“Caviar?”

He’s

chillaxing on the grass in front of me. Lying down, taking a break. I sit down,

look at the kid. His skin is gray under the light of the moon. Foam oozes from

the corner of his mouth. I press my ear to his chest. The heartbeat is an

irregular thunk, thunk, like potatoes in the sky.

Having

OD’d more times than I can remember, I know it’s not looking good for the kid.

TC’s

words echo in my head “one more arrest, Desmond, and you’re finished.” I know I

have to do what’s right. So I get up, look around, and walk away.

I use

my iPhone to find my car, which is still parked in front of the salon, a couple

blocks away. Thank God for technology I think as I get

back in my Audi, still high as fuck but more inspired than I have been in

years.

Maybe

I should make some music videos, I think, driving home, blasting

Kendrick Lamarr, Christian Death and Japanese experimental noise on shuffle. My

eyes are wide in the rear view mirror.

Yes.

Desmond Furie, still here. Fuck Grumpy Cat. Life’s cool.