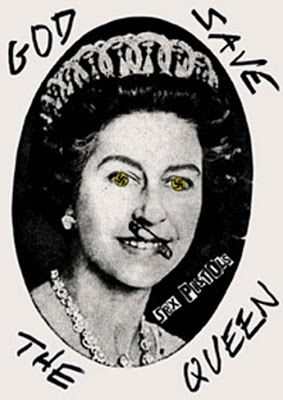

Artist, punk, druid, and nature-lover Jamie Reid has been planting dissent since 1975, when he gave the Queen of England swastika eyes and wrote “Never Mind The Bollocks” in cut-out lettering that continues to be appropriated by t-shirt bootleggers the world over.

Born in 1947, Liverpool-based Reid has always been inspired by two things: the anarcho-Dadaist ideas of the Situationist movement, and the magickal utopianism of his Great Uncle, George Watson MacGregor Reid, a turn-of-the-century socialist reformer and Chief Druid of the British Isles. This might explain why his work has evolved from socio-political protest art to the predominantly Gaian, shamanistic work he creates today. Either way, whether he’s creating abstract paintings inspired by Druidic ritual, or angry collages that say “Fuck Forever”, Jamie Reid’s art urges you to open your eyes. A timeless message, if ever there was one.

What kind of

household did you grow up in, Jamie?

From an early age, I was dragged off on demonstrations. Both

my parents were in involved in CND (Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament). And my

brother was involved in (WHICH ORGANIZATION?). The first one I remember going

on was one of the CND Aldermaston marches in the 1950s. I thought it was great!

I never realized adults could have that much fun. That’s the thing—I’ve always

wanted my political work to have a sense of fun. I think it makes the message stronger. So

much of politics is devoid of any sense of humor at all. Likewise with so much

of Christian and Islamic religion. I did a show in 1990 in Tokyo, and remember

talking to the some young monks at a Shinto temple. We were talking about the Bible,

and one of the monks said “The Bible? No good jokes in the Bible!”

You met Malcolm

McLaren in the 1960s, at art school in Croydon. McLaren would eventually bring

you on board to work with the Sex Pistols. Do you remember the first time you

met him, and how the conversation went down?

Not really. I have very blurred memories of that time. Of

course, we really got along well, and we became both very involved with the

student politics of the time. We immersed ourselves in a student occupation at

Croydon College. And we were aware of political uprisings in other countries, the

Vietnam anti-war movement and particularly of what was going on in Paris. There

was something powerful in the ether in those times.

I heard you and

Malcolm traveled to Paris together for the 1968 student riots, but missed them.

We didn’t make it to Paris. That is a myth.

Either way, you and McLaren

were both heavily influenced by the Situationist movement that was flourishing

there. Tell me how Situationist philosophy would influence your work as an

artist.

One of the things with my early graphics was to demystify

Situationist messages—so much Situationist text was long-winded and hard to get

your head around. I felt like you could say the same things, but with much more

punch, if you said them visually and with a sense of humor. So I started the

Suburban Press, and we would make stickers, pamphlets and posters that

reflected Situationist ideas. Like our “This Week Only This Store Welcomes

Shoplifters” stickers that we put up in shops, and “Closing down sales, due to

lack of raw material” CHECK THIS, which we stuck up in department stores. It

was all about just having a go, and putting ideas in to practical practice.

Plus it was enjoyable. So enjoyable.

What’s your take on

psychogeography, another big part of Situationist philosophy?

I don’t really know what it means. It’s involved with energy

lines. Basically it’s the antithesis of modern planning. The Situationist idea

is based on just wandering around and walking to discover things about the

environment. Not going to do a job, or going to school or working, or having

that kind of structure.

How did Malcolm come

to involve you with the Pistols?

It was a weird one. I

was living with some friends in the Isle of Lewis (in the Outer Hebrides, small

islands north of Scotland) that had a croft (a small farm). It was completely

different to life in London and I ended up there for over a year. Then Malcolm

got in touch, saying he had formed this band in London, and would I be

interested in working on it. So I moved back and worked with the Pistols. It

was my way of being able to put across ideas that I cared about. A lot of the

stuff we did ended up being banned—which was great of course, because it ended

up on the front page of newspapers everywhere. And I liked it because it wasn’t

elitist – our stuff could get through to working class kids; it wasn’t in a

gallery, it was being fly-pestered all over the country.

Many of the graphics

you used for the Pistols artwork, you had designed years earlier in your work

with the Suburban Press.

Yes, like the “Nowhere Buses”. They originally came from LA,

actually. An activist group in LA had sent

us a timetable that looked like the bus company’s timetable, except the buses

were not going anywhere. And I reused it. The shoplifting stickers I had made;

they inspired the look of the “Never Mind The Bollocks” album cover, lots of

fluorescent, retail colors designed for a quick sale. Reusing that stuff just

epitomized the spirit of the time, for me.

When you came up with

the “God Save The Queen” graphic, did you have any inkling how iconic it would

become?

No. I had no idea. You’re too busy getting on with things.

Once one thing’s done, you’re on to the next thing.

Comparisons between

you and Banksy have been made a plenty—what do you think about that?

Banksy comes from a different time and different age. Before

he was well known, we actually did an exhibition together at the Arches in

Glasgow. I believe the posters for it are worth a fortune on Ebay.

How much has the

gallery system been part of your world?

It hasn’t, really. In the early days, there’s no way we

could have done what we did in the confines of a museum or art gallery, anyway.

It’s never really been part of my world, until recently I suppose. The Tate

Modern got around to buying some stuff, as did the V&A (Victoria and Albert

museum). But you know, it all just boils down to people knowing what “art” is,

and thinking for themselves. We have had so much damage done by the “Brit Art”

movement—the whole thing was spawned by Saatchi and Saatchi (advertising

agency), who were the people involved in getting Margaret Thatcher into power.

Brit Art, to me, is like nouveau cuisine—a lot of money for fucking nothing. I

think better art is done in times of recession than in times of prosperity, any

way. In this country far more seems to get done than when people have fuck all.

Have you been to Art

Basel?

No, I haven’t been to Basel. A lot of the work I have done

in the last few years was done with the Aquarian gallery, with this guy Steve

Lowe. It is now called 113. He has put on some of great exhibitions, with Billy

Childish and others—but none of the shows we have done there have gotten

attention from the mainstream art circuit. In this country, the critics are all

friends with the artists. Critics wont go to new galleries, and the whole thing

is so corrupt and so negative. I’m not depressed about it at all--I just choose

to do things my own way.

The Eight-fold Year

is your latest project, in which you upload a new painting, photograph and

piece of writing to www.eightfoldyear.org each day for a year. It’s totally different to your work with the

Pistols and Suburban Press, and has a much more Gaian, shamanistic type of

message.

My work has always been on two fronts – the much more

spiritual, esoteric work, and the political work, even though people see the

two as being diverse. The Eight-fold Year is based on seasons, and the critical

times of the seasons, like the equinoxes and solstices. If you have a garden or

allotment, you’re already working to that pattern. This project links in with

my background, because my family were political activists who were also

involved with a druid order for three generations, starting with my Great Uncle

George Watson Macgregor-Reid.

Yes – I’ve heard

about your Great Uncle. He started out as a union activist working with dock

workers in Boston and New York, and once ran for Parliament as one of the first

Labour Party candidates. Then he met Madame Blavatsky (founder of Theosophy), returned to England

and befriended members of the Golden Dawn (a 19th century magical order

whose members included Aleister Crowley and WB Yeats) and became a swami-type

figure. Then he was made the chief Druid of the British Isles and led Druidic

ceremonial rites at Stonehenge. You’ve

often cited him as a huge inspiration.

Everything in my life has dovetailed from him. He died

before I was born, but I grew up with a knowledge of the tradition of druidism

and how, in his case, it was linked with the birth of socialism. If there’s one

thing I’ve always been aware of it’s that if you need political change, you

also need spiritual change. Look at the history of the Labor party and

socialist tradition—it stems back to spiritual visionaries and philosophers

like William Blake and Tom Paine. Sadly, today politics is mainly about

commerce.

Your Great Uncle was

active during the turn of the 20th century, a time of huge political

and spiritual evolution.

Yes, there was an incredible sense of New Age and

enlightenment—and then the First World War happened. It was like a massive fucking ritualistic

suicide. People look back on the Incas and the Druids and say “they must be

terrible, they practiced ritualistic suicide”. But modern society happily kills

people in the millions for power, greed and control. Poor soldiers. It breaks

my heart.

What do you think

about Wikileaks, and cyber terrorist groups like Anonymous, who are protesting

corporate and government corruption in a whole new way?

Physical protest is more restricted and oppressed than it

used to be. So yes, in this day and age, and with the options available, cyber

attacking is an effective way people can fight back. With most Western politics

there's the veneer you see, and then there’s the corruption and secrecy behind

it all. It’s interesting, the way that terrorism is being used to inhibit any

means of protest, and keep people under control.

What are your

thoughts on computers? Obviously there were no laptops, and no internet when

you started working as an artist and activist.

I often collaborate with a Russian laser artist called

Alexei Blinov. He told me he had a couple of friends who were top-end hackers,

who became disillusioned. They had decided that the microchip was an alien

invention designed to get us so utterly dependent on computers that once they

were taken away, the whole planet would be thrown into complete chaos. So yeah

- personally, I m quite wary of computers. Mostly I use them for communication

and some graphics. But I have a suspicion surrounding them. If computer systems

broke down, all means of public transport would fail, communications would

fail. We’re not prepared for those kinds of scenarios.

Our reliance on

computers, modern farming, fossil fuels etc—its much less scary if you know at least

how to grow your own food and generate your own energy.

I couldn’t agree more. I evenly split my time between

painting and gardening nowadays. I do that every day. I have a garden and an

allotment, and there's nothing like growing your own stuff. You don’t need

massive amounts of space. You can do it.

What kind of politically

driven art do you create today?

The Tory government has just announced that they are going

to sell off British forest and woodlands to private companies, and I wanted to

do a graphic about it. The Tory party logo is a tree, so I have used their logo

being cut down with a sword saying “Tory Cuts”. Something like that. They are

cutting libraries and child benefits too. They’re cutting everything.

What does the future

hold for Jamie Reid?

Who knows. Survival. Birth of new paintings. Planting

things.

How’s your allotment?

We have just planted broad beans, onions, shallots and sweet

peas. It’s such a great concept, the idea of allotments. They are so democratic!

After the Second World War, there wasn’t enough food, so people were granted

their own little bits of land to grow vegetables on. The whole concept was born

out of crisis. So many good things are…